Fibres and textiles

Textile: an umbrella term that includes any type of cloth or fabric made by weaving, knitting, bonding, braiding or knotting yarns/threads/fibres (or other textiles) together, and lastly hides. They could be made by hand or by machine, and could be made from any type of yarn or fibre. (Yarn meaning fibre or blends of fibres that have been extruded or spun into long strands).

To describe a textile, we need to know more than just what fibre(s) it is made of, we also need to know the construction method used to make it. For example, you could have two fabrics made of 100% cotton that each look and behave completely differently because one is woven and one is knitted.

Fibre: in the context of textiles, refers to the thread-like parts of materials (raw or processed, natural or synthetic) that we use to make yarns, threads and fabrics.

Some fibres come from plants, such as cotton and linen, some from animal proteins such as wool and silk ( all of which tend to be categorised as 'natural' fibres) and some are made from oil products, categorised as 'synthetics'. Some fibres are derived from plant cellulose such as wood pulp, but undergo heavy chemical processes to make yarn and textiles so don't sit in either category comfortably. These include rayon, modal and viscose. They are sometimes referred to as 'semi-synthetic'. To complicate matters further, various fibres are often blended together in textiles and garments. There are lots of nuances to the subject of what fibres go into our textiles, and what problems, advantages and properties they bring. I'll be writing a lot more about these topics in other articles.

Woven fabrics

Threads/yarns/strips are woven together usually with a loom, on which 'warp' threads are affixed vertically, and 'weft' threads are woven in and out of the warp horizontally (that is the threads run in straight lines up and down and side to side at right angles to each other. Using different coloured threads or variegated colours can create patterns within the fabric such as stripes, tartans, plaids, and Ikat patterns (in which the yarn is specially dyed in periodic variations, which when woven creates striking patterns). This 'yarn dyed' method of making patterns within the cloth is different from printing patterns on cloth that is already woven.

Different textures and appearances can be created with various methods such as yarn thickness, twist and direction of twist of some yarns and importantly, the weave pattern such as skipping over warp threads in a pattern rather than in and out of every one. For example, a 'twill' weave is created by passing over or under 2 or more warp threads, which creates a visible diagonal 'wale' or lined pattern. Denim is a well known example of a twill weave.

Most woven fabrics do not have much stretch due to the way the threads are lying in straight lines, referred to as the 'grainline' (unless an elastic thread is used, however the resulting stretch of the fabric will generally be minimal compared to a knitted fabric. Think of a stretch denim, in which elastane is added to the yarn which allows for a small amount of stretch). However, when orientated 'on the bias', with the grainlines running diagonally, the weave relaxes with gravity and there is some stretch diagonal to the grainline, which when used across the body in a garment gives a notable drape and flowing movement. It uses much more fabric to create a garment this way so bias cut garments tend to be more expensive.

The feel, drape or 'hand' of the fabric, and other properties are also affected by the types of fibre used, how tight the weave, the pattern of weaving, the number of threads per inch etc.

Woven fabrics tend to fray where cut, because when you cut them, the cut warp and weft threads are not secured and can unravel from the weave. The original lengthwise edges of the fabric, called the selvedge, does not usually fray due to the way the weft threads wrap around the warp and back so there is no loose thread unless they are cut.

The linear structure of the warp and weft in woven fabric means that it can usually be torn along the grain in either direction, or if the weave is loose enough, single warp or weft threads can be pulled out, creating gaps in the weave. These properties can be useful in ensuring that a cut is made 'on grain' which is vital to ensuring that items made from the cloth drapes in the way intended. If you have ever experienced a garment twisting on the body when not designed to, it was likely cut off-grain.

Different ways of constructing textiles and some examples

Twill weaves, including denim. On the right a close up of a twill weave pattern; note the diagonal lines created

Left, an example of an Ikat woven cloth. Right, a weaving loom with warp threads set up

Tartans and plaids are created by weaving coloured warp and weft yarns in various orders and weaves (although the look could be mimicked by printing a design onto pre-woven fabric)

Loosely woven fabrics like muslin or cheesecloth (left) have much lower thread count (threads per inch) than say a quality shirting fabric (right) which has a smooth tight weave and a more 'crisp',structured feel

So when we talk about fabrics/textiles, we have to talk about both the fibre content and the type of construction method that was used. Below are some general explanations of construction methods, and some examples of textiles in those categories. This is not exhaustive, but hopefully gives a useful summary.

Knitting: to make a knitted textile, loops are made in threads/yarns which are held on needles or hooks through which more loops of yarn are pulled to form another row of loops over and over. Due to the looped pathway of the yarn, and because loops can be lengthened and compressed when pulled, the fabric created by knitting usually has stretch, even if the yarn used does not actually have inherent stretch. This is referred to as 'mechanical stretch'. Additional stretch (and recovery) may be given to a textile if elastic yarn is knitted alongside the main yarn, known as plating (the 2 yarns are knitted together as one).

There are essentially only two ways of making a loop in a new stitch; pulling through from front to back, or the reverse - back to front. These are referred to as 'knit' and 'purl' stitches. The little 'bump' where the top of the loop appears shows on the front or back of the fabric on the side it was pulled toward. If all the bumps are made on one side only, then there will be a smoother side of the fabric (usually used as the front, or visible side) and all the little bumps will be on the back. Other techniques such as twisting the loop, extending its length or even changing the order of the loops on the needles can also affect the appearance and properties of the fabric created. The order in which these operations are performed also creates patterns and textures; for example, alternating knit and purl stitches (or multiples) creates ribbing, which has even more stretch than a plain knit fabric, hence you will often see it used for collars, waistbands and cuffs, where good stretch and recovery is important.

Machine made knits come in many varieties, with different characteristics and qualities with a variety of suitable applications (still only talking about construction methods here, different fibre types could be applied to any of these categories). Without going into all the details here, some of the main types include:

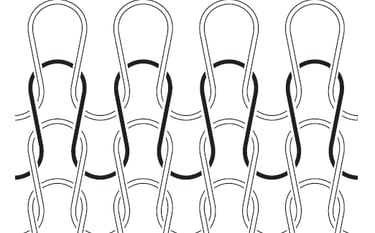

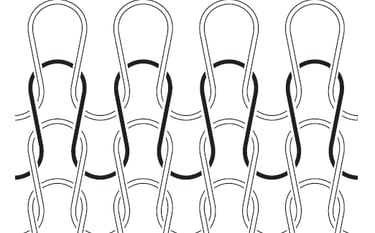

Weft knits are knit in rows across, either back and forth 'flatbed' or around a circle, forming a seamless tube - a similar process to hand knitting:

Single knits: made on a single row of needles. Makes a finer knit, usually with a front and back with different appearance. Single knit fabrics tend to curl to the front at the horizontal edges and towards the back on the vertical edges. In this category would be jersey knits, lightweight sweater knits and pointelle knits (fine knit with spacing patterns). Most T-shirts would be single knit jersey for example.

Double knits: two rows of needles knit two layers attached into one resulting in denser, more stable structured fabrics than single knits. The fabric can have 2 sides with the same texture using this method, but they could also be different colours/patterns. Types of double knit include some ribbing and interlock, heavier 'bottom weight' knits as well as some sweater knits.

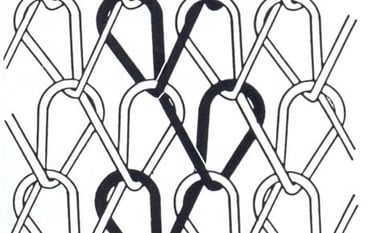

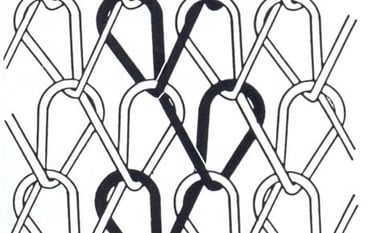

Warp knits (knitted up and down columns using multiple parallel yarns, the stitches at an angle rather than vertical orientation):

Less horizontal stretch than weft knits, and much less stretch vertically. Also less prone to shrinking or unraveling than weft knits.

Can be used to create complex patterns and designs. Types of fabric in this category include tricot, net, tulle, some types of lace.

A knitted textile is easily recognised when the stitches are of a size that could be produced by hand; where the knit stitches and patterns it can produce are large enough to be seen easily (left).

If you look closely at a stretchy garment such as a T-shirt, you will likely find that it is a knitted fabric, the stitches are just much smaller and the thread much finer than with a hand knitted garment. These types of knits are made by machines, (examples below) some in much the same way as hand knitting, only with a great many (and much thinner) needles.

Above left, ribbed knit used on collar and cuffs where stability, stretch and recovery are important.

Above right and below left, industrial knitting machines

Some knits are made on circular machines that create seamless tubes of knitted fabric., others are knitted flat on 'flatbed' machines

The number of needles used relates to the gauge of the fabric, the greater number of needles (and therefore stitches) per inch, the finer the fabric produced

Above left, the yarn path of a weft knit (loops added horizontally, such as in hand knitting)

Above right and the yarn path of a warp knit (loops added vertically)

Bonded textiles

In a bonded textile, yarns or fibres, or whatever is being used are bonded together using either mechanical methods (such as felting, in which the fibres are agitated and matted together forming a permanent physical bond) or laminated or fused in some way such as glueing or melting. Bonded textiles do not usually stretch or fray, but they may be prone to tearing in some cases.

Examples::

Wool felt: the natural structure of the wool fibres having scales that when roughed up via heat, detergent and agitation, cause the fibres to stick to each other and shrink together in a permanent bond. If you've ever put a wool sweater in the wash by accident you'll probably have seen this in action!

Synthetic felt: made from synthetic fibres and looks similar to wool felt, however the fibres do not have the scales that wool does so are usually bonded together with glue.

Polar fleece:

Fibres viewed through an electron microscope showing the scales of animal fibres like wool and alpaca which cause them to be felted irreversibly under certain conditions. I can't find the original source of this image, I found it on a Reddit thread.